This past June, I completed my Master’s thesis, which is presented in its entirety below. I am publishing it on my blog so that those who wish to can read it. A month certainly wasn’t long enough to do everything that I would have liked to on this project, and I think it’s worth saying that I hope to do more research into this issue in publishing in the future. But, for now, here is what I have.

© Allison Bucknell 2015

Introduction

Today’s world is a world flooded with options: restaurants, television shows and movies, careers, technology devices, and any kind of book you might want in any format you desire. According to the 2014 International Publishers’ Association annual report, the United States alone produced 304,912 new titles and re-editions[1] in 2013, and China and the UK in particular have very active publishing industries with 444,000 and 184,000 new titles and re-editions having been released, respectively.

With the sheer number of options, it is no wonder that readers often have a difficult time either finding new books that suite their taste, or expanding their horizons with organic discovery of quality titles. Because of advances in technology and the interconnectivity of the Internet and its recommendation engines (think Goodreads, book blogs, review sites, and recommendation sites like Trajectory and whichbook), discovering new books is moderately easier than before the Internet and increase in published books. Algorithms on library, bookstore and other retail sites (e.g. Amazon) enable better browsing, but those who use those sites know that it’s near impossible to search for books that meet specific criteria that goes beyond general theming/genre categorization. Suw Charman-Anderson, a contributor to Forbes magazine, remarks on the real problem:

It is, in fact, trivially easy to discover books: Just go to any book store, online or off, and you’ll discover more books than you can shake a stick at. The problem is not one of finding books, it is one of discrimination, of deciding which books are worth reading, and it’s a problem [that] is compounded by the vast choice on offer. How does one navigate this flood of information, especially in regards to the book world? (Charman-Anderson, 2013)

In light of this, how should publishers and authors respond? With the choices available, how does one navigate in a productive way?

The book business has always been unique in that its products are much more complex; when a buyer goes to purchase a piece of furniture or a toy for a child, the process is straightforward. Consumer sees, consumer buys, consumer enjoys. A book is more than just something to consumer. It is an experience, the offspring of creative minds, and as such, they require tailored dedication in the acquisition, refinement, promotion, and selling efforts. Because of their experiential nature, a book needs to draw consumers in a way that furniture and toys usually can’t.

One aspect of the traditional sales approach that has gained a lot of attention in many areas of business is branding, an aspect that has evolved with the rise of the Internet and the way it has changed the needs and habits of the consumer. Branding wasn’t emphasized as heavily because there was no need for it: before the Internet and Amazon changed the way customers buy books, third-party retailers provided the primary avenue for the public’s book buying. In other words, there were many books to choose from, but the competition was limited within certain venues. Now, a customer can buy a book directly from the author or publisher, or through a variety of retailers, both online and offline. The openness of these avenues has cultivated an intensely competitive atmosphere, which harkens back to the problem of choice (though it ought to be noted that purchasing choices offer different challenges that won’t be discussed here). As a result, books are coming into the market in numbers greater than ever before, and they are moving into and through it by a growing number of avenues. Self-publishing websites, vanity presses, publishing services, traditional publishers, independent publishers all have a share in creating a market that produces too much for a casual or committed consumer to wade through. While there may be other solutions to the problem of effective discovery, branding takes the high ground and, if done well, could be part of the answer on a fundamental level by changing the way consumers think about finding new titles, and the way that publishers and authors approach the publication of their products in a world where discovery often happens organically.

What is Branding?

According the to American Marketing Association, a brand is a “[n]ame, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller’s good or service as distinct from those of other sellers” (“Brand and branding”, n.d.). Brands such as Nike, Apple, or Glade, for example, all have a reputation in the public eye that has established them as distinct among their competitors. Their products may not be universally considered to be good products, but you would be hard-pressed to find someone who is unfamiliar with these names.

According the to American Marketing Association, a brand is a “[n]ame, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller’s good or service as distinct from those of other sellers” (“Brand and branding”, n.d.). Brands such as Nike, Apple, or Glade, for example, all have a reputation in the public eye that has established them as distinct among their competitors. Their products may not be universally considered to be good products, but you would be hard-pressed to find someone who is unfamiliar with these names.

When a company begins to build its brand, it typically depends on visual elements to establish itself first and foremost, in addition to a catchy slogan that captures and communicates their essence. However, these elements only carry a brand so far. Though it takes longer, I’d argue that it’s more important for a brand to establish their reputation through the quality and character of their product; a good logo/slogan combination can only carry a company so far.

The biggest publishing conglomerates, referred to as the Big Five (Penguin Random House, Hachette, HaperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan) all have distinctive logos that they’ve nurtured over the years, and it’s safe to say that those logos have some recognition in the public eye. The claim that is impossible to make is this: that the public, or even the smaller group of book enthusiasts, know the Big Five in terms of what they produce. Books? Yes, of course. But what kind of books? Is this kind of distinction even possible, and does it matter?

Why Branding is Important

Brands are utilized to distinguish themselves from their competitors; they are not there to tell you how much better they are than the others, nor do they try to hard sell their product with a list of positive qualities. The cultivation of a consistent reputation is essential to brand building, and the way to building a consistent, dependable reputation is through the product itself. The books that a publisher puts into the market should have qualities that set it apart from the books published by other houses. But the Big Five are virtually huge conglomerates of smaller publishing divisions, so how can they accomplish this? How can they utilize brand development strategies to make themselves more visible and accessible to readers? The content that the Big Five publishes is varied and too broad to be able to establish branding that extends beyond a general image. Penguin Random House (PRH) has made great efforts to establish itself as an active participant in branding through everyday engagement with the ebb and flow of social media, breaking norms and barriers by recruiting through Tumblr[2], and the huge integration[3] of Penguin and Random House in 2013. But those efforts aren’t enough. Publishers need to establish brands for their product lines in order to reach the audiences who are, or who could be, interested in what they have to offer specifically in those lines. Readers are always looking for new titles, so the opportunity exists, but publishers need to break their attention down into smaller, more manageable divisions that lend themselves to branding. The Big Five can only do so much to create house-wide brands.

This is why imprints are vital to the branding goals of a publisher. It is only through the implementation of imprints as the branded branches of a publisher that they can ever hope to create brand recognition that will help readers find what they want. However, even in the case of a successful imprint branding effort, there won’t necessarily be a wider recognition of the Big publisher, which is a sacrifice that will need to be made in the interest of the industry and parent company. That kind of sacrifice can be made without interrupting the larger vision of the bigger company, which paves the way for imprint branding ventures.

Beyond the branding of imprints, publishers should also be supporting authors in their missions to brand themselves. Self-publishing has made author brands a necessary step on the road to successful author careers, and big publishers have a lot to learn from successful self-published authors when it comes to creating communities and drawing audiences through their author brand. There is potential for a symbiotic relationship between author-brands and imprints, a relationship in which imprints support authors, who in turn support the imprint through the effective community-gathering that authors are often capable of creating. Publishers have in their possession two powerhouses: the author and the imprint, both of which have been underutilized in many cases. In order for publishers to find new life in the coming years and the changes that those years will bring, they need to begin looking outside the ordinary solutions that they’ve used for business in the last era. A new era in bookselling and production has begun, so it is important that publishers tackle the problem of finding and creating customer bases in new and creative ways.

Imprints

So imprints are important, but what exactly are they, and how do they function as an integral part of a large publisher’s branding strategy? How do imprints differ from small, independent  presses, and are those differences consequential? Can better-defined brands solve the problem of effective book discovery? Most of the Big Five are represented here by at least one of their imprints, including Saga Press, Broadway Books, and a variety of sci-fi/fantasy imprints like Firebird, Ace Books, Harper Voyager, Orbit, and Tor/Forge.

presses, and are those differences consequential? Can better-defined brands solve the problem of effective book discovery? Most of the Big Five are represented here by at least one of their imprints, including Saga Press, Broadway Books, and a variety of sci-fi/fantasy imprints like Firebird, Ace Books, Harper Voyager, Orbit, and Tor/Forge.

What is an Imprint

Imprints, for our purposes, are smaller segments of a larger publishing conglomerate. A publisher can have many imprints, some of which can be gathered into groups like, for example, PRH’s Crown Publishing Group or their Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group (See Appendix A). Imprints are the building blocks of a publishing house. Each imprint at a publishing house specializes in a certain area. For example, Crown Publishing Group’s Broadway Books imprint is “the paperback imprint for the Crown Trade imprint. In addition to paperback reprints, Broadway publishes original titles across several categories, including memoir, current affairs and politics, travel and adventure narrative, and popular fiction” (Source)[4]. Saga Press, an imprint from Simon & Schuster, describes itself as “an all-inclusive fantasy and science fiction imprint publishing great books across the spectrum of genre, from fantasy to science fiction, commercial to literary, speculative fiction to slipstream, urban fantasy to supernatural suspense” (Source)[5]. Neither of these imprints are niche, but they publish a specific type or genre of book that defines the imprint. One thing to keep in mind is the fact that those who are acquiring for an imprint have different tastes, and while an editor may be at an imprint for many years, they are bound to leave at some point or another. In this case, it’s understandable why an imprint might have a vague description, as Saga Books does. This flexibility is important because it both allows editors and creatives within the company a wide variety of publishing options, and gives readers a platform on which to build expectation and trust with that imprint.

Imprints enable publishers to divide their companies into parts that make sense to consumers and business. Without imprints, publishing houses would be chaotic and unable to operate in any orderly fashion, and any book, regardless of quality or author, would be lost in the mess. When imprints fall into neglect, they are either merged with other imprints to form a revitalized group, or they are discontinued. This imprint-book group-publisher structure shifts, but for the sake of business (and even branding), shifting imprints around can be an effective strategy. Considering the size of publishers, it comes as no surprise that most of the Big Five have a wide variety of imprints and divisions (See Appendix A for comparison).

Standard, large divisions that one would find at a publisher are as follows: adult, children’s, academic, international, trade fiction and nonfiction, digital, and audio[6]. Under these divisions, imprints are formed (and it should be noted here that publishing groups are sometimes classified as “divisions”). This method of organization allows for the existence of similar imprints within one company, especially in the adult and children’s divisions. For example, PRH has at least two sci-fi/fantasy imprints: Ace Books from the Berkley Publishing Group and Firebird from Penguin Group. Further, genre classification and imprint creation is pretty standard in the industry, which creates a good deal of overlap across imprints from the Big Five, which can lead to the issue of publication of similar books. This is why branding is vital: it is the difference between HarperCollins’ Harper Voyager and the remaining Big Five sci-fi/fantasy imprints: Hachette with Orbit and Macmillan with Tor/Forge. The case for branding is strong. These publishers are producing books that all typically fall into standard categories across the board. We have five sprawling publishers that occupy much of the market. Their methods of categorization are all standard, which is not a bad thing, but it cannot be the only thing that publishers rely on when trying to market their products. There are a few genres, like formula fiction genres and classics, that sell themselves, but most other types of book, be it fiction or nonfiction, need to have unique selling points and quality characteristics that set them apart from the others. The same goes for imprints: it’s okay (and very helpful, in fact) to classify under a specific genre, but there needs to be more to your imprint than just the fact that it’s historical fiction, romance, or anything else.

Standard, large divisions that one would find at a publisher are as follows: adult, children’s, academic, international, trade fiction and nonfiction, digital, and audio[6]. Under these divisions, imprints are formed (and it should be noted here that publishing groups are sometimes classified as “divisions”). This method of organization allows for the existence of similar imprints within one company, especially in the adult and children’s divisions. For example, PRH has at least two sci-fi/fantasy imprints: Ace Books from the Berkley Publishing Group and Firebird from Penguin Group. Further, genre classification and imprint creation is pretty standard in the industry, which creates a good deal of overlap across imprints from the Big Five, which can lead to the issue of publication of similar books. This is why branding is vital: it is the difference between HarperCollins’ Harper Voyager and the remaining Big Five sci-fi/fantasy imprints: Hachette with Orbit and Macmillan with Tor/Forge. The case for branding is strong. These publishers are producing books that all typically fall into standard categories across the board. We have five sprawling publishers that occupy much of the market. Their methods of categorization are all standard, which is not a bad thing, but it cannot be the only thing that publishers rely on when trying to market their products. There are a few genres, like formula fiction genres and classics, that sell themselves, but most other types of book, be it fiction or nonfiction, need to have unique selling points and quality characteristics that set them apart from the others. The same goes for imprints: it’s okay (and very helpful, in fact) to classify under a specific genre, but there needs to be more to your imprint than just the fact that it’s historical fiction, romance, or anything else.

Most of the Big Five sci-fi/fantasy imprints have overlaps in the kind of books they publish. Harper Voyager, tends to specificity with publication of urban fantasy/supernatural and horror titles. Orbit’s goal is “to publish the most exciting Science Fiction and Fantasy for the widest possible readership. We are committed to attracting more readers to Science Fiction and Fantasy” (Source). These imprints align at many points, and it’s difficult to identify the flavor of each imprint without reading the books they produce.

Big Publishers, Indies, and Branding (or lack thereof)

Because branding is such an important strategy nowadays for companies that rely on consumers for survival, it stands to reason that those invested and interested in publishing would be concerned about the standard branding treatment that most Big Five publishers exhibit. An exception is Penguin Random House, which has been careful to cultivate a solid relationship with readers, be it through visual recognition or through engaging social media interactions (posting Buzzfeed quizzes, retweeting dating apps, timely book promotions, etc). But for the most part, the Big Five aren’t interested in all the hype that branding has created. Why?

There are a few reasons that branding hasn’t exactly been welcomed with open arms in the publishing industry. Michael Levin, a “nationally acclaimed thought leader on the subject of the future of book publishing,” mentions the other exception to the brandlessness of big publishers, and offers his opinion:

The only exception to the rule among the major publishers is Wiley, which has a solid reputation among business readers for its books. Indeed, Wiley has at least three current best sellers on the subject of branding… This shows it’s possible for major publishers to have their names matter as much as or more than those of their authors (Levin, 2013).

Levin’s point offers some hope for the big publishers: Wiley has cultivated its relationship, taking care to take steps that would bring them recognition for the quality of work that they produce and the solutions that they offer. It’s possible to become a reputational leader in publishing, but the catch is that doing so requires dedication and heavy investment, which is something that publishers know. So what’s stopping them? There’s a bigger issue, which Levin sums up nicely:

The result is that people inside publishing companies throw their work over the proverbial wall with no regard for what will happen once their own work is done. The various departments are doing their jobs, but no one is doing the job — burnishing the publishing company’s brand into the consciousness of consumers by having it stand for something distinct and important. … You could get away without having a brand that consumers could readily identify back when publishers had it plummy — before the Internet came and ruined all the fun. Not anymore (Levin, 2013).

Levin affirms the necessity of brands in the age of the Internet, but goes another step to take a dig at the stubborn nature of traditional publishers. Before the Internet, branding more or less fell in the same game as advertising and marketing; books had maybe one or two avenues of discovery, and the capabilities of the publishers were less than they are today.

But today, the importance of publishers engaging in forms of meaningful branding can hardly be argued. The answer to the problem of branding, however, is not as straightforward as proscribing imprint branding and then leaving it at that. Aside from a few like Harlequin, Tor, and Farrar, Straus & Giroux, for example, imprints have not been successful to distinguish themselves from similar imprints. But what does it take to makes a successful imprint? All three mentioned above are known in the wider world for what they publish, but they aren’t starkly different from the other sci-fi/fantasy, romance, and literary/nonfiction/children’s imprints. In the end, the quality of a title speaks for itself, and it is through the consistent production of those quality titles that a brand becomes as established as Tor/Forge is. The author plays a distinct role in the success of any imprint, so it makes sense that publishers opt to invest in the author-brand more than they do their own imprints. Hefty advances and a variety of marketing packages often go hand-in-hand to promote the author and his or her new book, but where is the budget for imprint building? Perhaps publishers believe that the imprint will benefit indirectly from the initial investment made in the author-brand, but in order for imprints to be more successful, they need to be able to express their distinguishing characteristics more effectively. Through good leadership, some imprints have found their voices and maintained them, but that isn’t the case with others. The author-brand plays an important role in helping the imprint establish that voice.

The Author-brand

The author-brand is by far the kind of branding that gets the most attention in the media. In publishing, there are authors who have established brands so successfully that any new book is immediately picked up, regardless of whether the reviews are good or bad. Instead of the book acting as the one being orbited, he author is the rallying point. The community that the author has grown around him- or herself is the reason loyal fans keep coming back. The brand is what sells the books, not the book itself. Think of Steven King, or Nora Roberts, and even Stephanie Meyer. These are extreme examples of author branding, of course; it would seem as though these authors have reached a point of popularity where the books don’t matter as much as the fact that it was written by said author. Yes, it’s important that they continue to produce books, but in the end, the book itself is arbitrary.

Author branding is a strategy that is utilized to perpetuate discoverability and create loyalty. Social media is a powerful tool that many authors (even unpublished ones!) use to create a persona online. Other authors use blogs, or host book clubs in the community. Some go so far as John Green, who has a Youtube channel[7] filled with things you would never expect from a YA author. How an author works the strategy will depend on the author and their level of commitment to their brand, but the goals are the same: create a loyal community. In an article in BBC’s Culture section, Hephzibah Anderson underscores the importance of author brand recognition:

Forging brand recognition is an increasingly necessary part of being a writer… For though it’s never been easier to get published… it’s never been harder to get noticed. While readers have little loyalty to publishing imprints…. authors are a different matter (Anderson, 2014).

There are differing opinions about whether an author is best served by consistency or variance in how and what they write. A case for consistency was made in a piece written by Writer’s Relief Staff for Huffington Post’s Books section.

Think of it this way: When you step into a theater to see the latest Woody Allen movie, you’re expecting to watch something quirky and character-driven. If instead you found yourself bombarded by car chases and fiery explosions, you would be confused and perhaps a bit annoyed. You’d want your money back!

The same logic applies to your author brand. You’re promising your audience a particular kind of reading experience, and you shouldn’t let them down. From project to project, maintaining continuity in your voice as a writer is vital to building a successful author brand and establishing a strong fan base. (Writer’s Relief Staff, 2014)

The writer goes on to explain that consistency does not equate with the same story lines and characters. One example of this can be found in Mark Haddon’s, author of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, writing. His books have a particular look about them (see Image A), and upon reading the novels, it becomes quickly apparent that Haddon’s voice and style is very distinct. The subjects he deals with revolve around families and a wide range of issues they encounter on a daily basis, which speaks to a consistent type. Each story is unique, yet each carries Haddon’s voice and style, which makes Mark Haddon: the author.

An author’s style and voice is key to the development of that author’s brand; it is what distinguishes that author from the rest of the crowd, and for an author who has honed their craft to that point of distinction, the better positioned they are to create a loyal following. This kind of following, often referred to as “platform”, is something agents and publishers take into consideration when considering new acquisitions. Why? Because they realize that presence is an important element of success for an author. Publishers may be careful with how they invest their marketing resources, but they have established the fact that author brands are important to them by their increasing interest in the online platforms that authors have developed pre-contract signing. This shift may be a sign that publishers are looking for a cheaper, easier way to market authors, or it may be a sign that they’re getting ready to make a bigger change in their tactics. Either way, well-developed author brands are key.

The technicalities of a good author-brand development are many, but there is one aspect that I want to emphasize, and that is the role that a dedicated editorial department plays in the development of the author-brand. Beginning with the acquisitions process, it is the editor that decides to take on manuscripts that hold promise. To go one step further, it is during the acquisition process that the editor makes a critical choice: the manuscript that they are taking on either will or will not reflect the brand (or the brand trajectory) of the imprint. Of course, there has to be a brand to adhere to. If an imprint has no clarified vision for what they want to produce, there is no reason to expect that editors can make good decisions on manuscripts, unless the imprint is young and its vision is only just being cast.

Strategies for Branding in Publishing

Imprints will play an increasingly important role in branding both today and in the future for publishing. They are already set up in such a way that takes the responsibility from the bigger houses and puts it on the imprints. However, not much has been done with that responsibility, and it’s time for that to change. From the Association of Authors’ Representatives [8](AAR) blog, “Penguin Classics, Harlequin, the Dummy Books and Tor are examples of imprints who have succeeded to brand themselves straight to the consumer,” the writer says. “Readers know what to expect when they pick up one of these books. Their trust in the imprint to deliver a type of read has been tested and found to be reliable” (Digital Rights Committee, 2012). Trust leads to loyalty, and loyalty is what both authors and publishers want because it leads not only to sales in the present, but also in the future.

One of the big issues that imprint branding would solve (or at least relieve in a considerable way) is the issue of discoverability. When imprints are successful in communicating and producing the books they say they want to, readers will have a trustworthy place to go to try new titles or authors. A well-branded imprint like Tor serves as a recommendation engine all by itself. The writer from the AAR blog assures readers of the benefits that imprint branding would bring, across the board: “Through imprint branding we are able to take away some of the monetary risk for our readers and build trust and loyalty that could then make it easier for a new voice to be discovered. This would not only benefit the imprint/publisher but the brick and mortar as well as the on-line stores, the authors and the consumers.” This all sounds good, but it’s hard to prove because there are no case studies done on the subject, and the sample of imprints that have implemented this successfully is limited. Where can a publisher begin? The first step would be to evaluate the health of any and all imprints under the publisher’s umbrella. Before any steps can be taken to create a better imprint, there should be goals. As with any strategy, a lot of planning is required, and outside help might even be necessary for imprints that have been kicking at the same stone. Another important part of any strategy is to make sure that staff across the board are involved; get the interns, editorial staff, design team, sales, marketing. Anyone who will be contributing to the books and to the presence of the imprint needs to be on board. Imprints are generally small enough that close working relationships across departments is essential.

A Symbiotic Relationship

There is a relationship to be had between imprints and authors, and the brands that they represent. The industry as a whole is reliant on authors, whereas authors are not wholly reliant on the traditional industry, thanks to independents and self-publishing options. The Big Five must bring something of value to authors in order to retain those who have longstanding relationships, and to attract those looking to begin one. To offer authors a contract with an imprint that has made a name for itself would benefit both the publisher and the author in more ways than one.

Ideally, an author and imprint would work together to promote the work of the author and the vision of the imprint. It is possible that it seems the imprint carries more responsibility, but it’s important to remember that the responsibility of the imprint differs from the responsibility of the author; they serve different functions, but those functions are vital to the health of the relationship.

The Role of the Imprint

It is helpful to view the relationship that the imprint has with the author as a marriage of sorts, in which both parties exist to serve and support the other in whatever capacity they are able, without either one absorbing the other. The imprint, because it operates in a wider capacity, takes precedence in the bigger world of the industry and of the masses, whereas the author would find him- or herself operating on a more personal level.

An imprint’s brand should serve the author by providing a defined place to be found both by other readers and retailers, a community of likeminded authors, and a staff committed to helping the author develop their brand. Ideally, an imprint that has distinguished itself from its competitors in some way will continue to pursue that, both in the manuscripts that it acquires (an eventually publishes) and in presence that it cultivates both online and offline. This means that imprints must actively reach out to and engage readers that could become consumers of the books they publish. Depending on the imprint, this outreach would look different; a literary fiction imprint would not seek out potential readers the same way a fantasy imprint would, for example.

Because publishers operate under contracts that could last anywhere from one title to a series of titles, an author is not necessarily bound to stay with a specific company. This poses a problem in the interest of creating longstanding imprint/author relationships. While there is no surefire way to prevent an from author deciding to leave their publisher for another, better opportunity, the goal of imprint branding is to create an environment where the author doesn’t want to leave. Branding shouldn’t create trusting relationships just between a company and the public, or the author and the public. Rather, the formation of trusting relationships needs to happen between the publisher and the author as well. The size of an imprint allows it to be more flexible, and this is a trait that publishers should take advantage of in the interest of their future wellbeing. Traditional publishing still offers a valuable opportunity to authors who wish to be validated and discovered by the wide world of readers, but publishers must reconsider their tactics when it comes to attracting and retaining new, brilliant and talented writers. The current environment is not exactly conducive to good relationships. If authors knew that they were being taken care of in a genuine way, rather than in an exploitive way, how much more likely do you think it would be that they would stick around?

An Aside about Independents

Independent publishers are in what some consider a “golden age.” Kelly Gallagher with the Independent Book Publishers Association draws on her 25 years as an industry veteran and says, “I believe this very well could be independent publishing’s golden age, but I hasten to add that that success is neither easy nor guaranteed” (Gallagher, 2014). Independent publishers, more affectionately known as “indies,” are powerful in that they have both the power of a publishing house, and the tight community and capabilities of an imprint, which puts them in a unique position. They have the ability to focus all of their attention on niche audiences/genres if they so choose. Take Akashic Books, or Publishing Genius Books, for example. Both indies are dedicated to their genres (urban literary fiction and political nonfiction; and anything quirky, respectively), and are willing to take small, intentional steps to see their companies thrive. Because they have the ability to go deep, they have a unique branding opportunity because, unlike the Big Five or any other large publisher, their company IS the brand. They don’t necessarily have to figure out how to blend imprint brands with the larger publishing brand. Imprints, and by extension the big publishers, can learn a lot by watching how indies operate.

The bottom line and profits are a source of concern for any involved in publishing; book making and curation is not a money-maker by any means. If publishers were to allow imprints to invest in the way that is necessary for these kinds of relationships, who’s to say how the company would be affected? Publishing books is not a sure investment, but the problem is that brands don’t develop overnight, and, considering the size of publishers and the number of imprints that currently exist, any movement toward establishing imprint brands would take a lot of time and concentrated effort. It would probably require shifts in how each imprint approaches acquisition and the relationships with each author they sign, as well as more focus and resources directed toward audience outreach. Those only scrape the surface of what would be required to shift into a branded imprint approach to publishing.

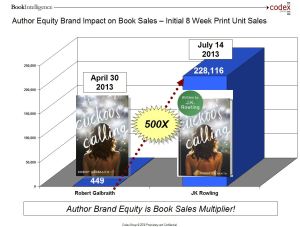

However, I would like to make the case that, even if the upfront changes are more costly and risky, the publisher would be in for a long-term return on investment. In an article posted on Forbes.com, David Vinjamuri illustrates the effectiveness of brand recognition in an example using J.K. Rowling/Robert Galbraith’s book The Cuckoo’s Calling:

Yes, both online and critical reviews can help, but only if the book attracts enough attention to make these review relevant. In other words, before a book can possibly become a bestseller, it needs to reach critical mass. Without the foundations of a strong brand, most authors will never get this far.

We saw the proof of this point last year. In April of 2013, Little Brown (Hachette) published The Cuckoo’s Calling by unknown author Robert Galbraith. Despite the big-five publisher and solid early reviews, the book sold just 440 print copies in April. When it was revealed several months later that the book’s author was none other than J.K. Rowling, the sales arc bent. As you can see from the chart below, The Cuckoo’s Calling sold 228,000 print copies in July. (Vinjamuri, 2014)

J.K. Rowling is a branding superstar, but the point is clear: brand does matter. Rowling has a loyal following. True, most books are never going to reach a following as massive as hers, but cultivating loyalty, even in smaller numbers, is incremental growth, and it does pay off in the end, not just for the author, but for the publisher as well.

The imprint should be a home for the author. But how does an author use their brand to benefit and support the imprint?

The Role of the Author-brand

Since it is the imprint’s role to serve the industry and mass audiences, the author’s role is on a more personal level, and at first glance, a less important one. However, as with symbiotic relationships, you can’t have one without the other. It’s fair to say that the author brand serves a lesser role, but it’s position as lesser does not diminish its importance.

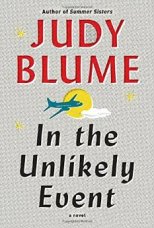

The author has the advantage of being a single entity that is able to express in ways that a conglomerate of people cannot. It is possible to connect human-to-human, and therein lays the power of community. An imprint should be able to create loyal communities around the books it publishes, but those communities differ from the one that the author can create. Through social  media, readers who may have discovered an author through a well-branded imprint get to experience the author in a more personal way, which can strengthen, or even create, the loyalty that the imprint initiated. In a way, authors who develop their own brands take the relationships that the imprint began and deepen it. The imprint almost takes a backseat at this point because it no longer is the reason that the reader gathers to the author; the reader gathers on his or her own. And, once a reader is at the point of loyalty to an author, they’re usually captured for life. Judy Blume’s new book In the Unlikely Event is guaranteed to do well not only because of Blume’s quality writing, but also because of the loyalties that she established with a plethora of kids and their parents years ago.

media, readers who may have discovered an author through a well-branded imprint get to experience the author in a more personal way, which can strengthen, or even create, the loyalty that the imprint initiated. In a way, authors who develop their own brands take the relationships that the imprint began and deepen it. The imprint almost takes a backseat at this point because it no longer is the reason that the reader gathers to the author; the reader gathers on his or her own. And, once a reader is at the point of loyalty to an author, they’re usually captured for life. Judy Blume’s new book In the Unlikely Event is guaranteed to do well not only because of Blume’s quality writing, but also because of the loyalties that she established with a plethora of kids and their parents years ago.

Loyalty to an author-brand is the cornerstone that unlocks many opportunities that allow the author to continue to build relationships with his or her readers. When readers are dedicated to an author, they are willing to do things that casual readers may not be willing to do, such as show up for new book release signings and events, or participation in social media events, like that which novelist Kiera Cass used for the release of the next book in her Selection series last year.[9] It’s easy to see how readers and authors create authentic, trusting relationships, but that seems to be one of the only things that an author brand achieves. Yes, a great achievement, but is that a good enough reason for imprints to invest in their authors and the brands they perpetuate?

There’s no perfect way to blend an author’s brand and an imprint’s brand, but that isn’t the goal of branding these two operatives. They exist for different reasons, and they represent different things, so it stands to reason that trying to merge the two is a bad idea. It’s ideal, in fact, that the two remain separate, but close. The reason an imprint should invest in helping their authors build their brands is obvious: while the imprint may not get very much direct attention, the success of the author will reflect back on the imprint, which builds that brand, and, ultimately, reflects back to the publisher themselves. If a publisher is known to have dependable, quality imprints, that publisher will by extension have a better reputation. Take PRH, for example. Not only has PRH gone ahead and worked toward a recognizable brand as a conglomerate, many of its imprints support that reputable name because of their success: Golden Books[10], Del Ray[11], and DoubleDay[12], just to name a few.

The joint efforts of the imprint and the author, and the support that they offer each other, perpetuate recognition of both brands separately, yet in association. The imprint is the lead influencer in this symbiotic relationship, yet much is gained because of that. The fact that these two are separate affords both of them space to move in the ways that are most effective for each without inhibiting the other. It is not a perfect relationship, nor is the process to get imprints and authors to work in such relationship an easy process, but it does seem like a good option moving forward.

Conclusion

In the Winter 1999/2000 issue of the Publishing Research Quarterly, the attitude toward publishing and branding is nicely summed up:

The need for trade publishers to compete effectively within the market, and provide the consumer with some level of differentiation between titles means that creating a brand identity is now an important marketing option. Despite this, the development of brand identities has been slow with many publishers taking the view that the general public have no perception of publisher’ identities and that ‘…brand-name loyalty in publishing exists mainly in the minds of public relations flacks.’[13] (Royle, Cooper, and Stockdale, 1999)

The attitudes have shifted, but it’s safe to say that some still consider brand names in publishing less than ideal and more pretentious than anything. But branding is important, and proof of such a statement can be seen everywhere in the world around us. Brands sell us things.

Publishing is a special industry, though. Books are not wares to be hawked to the masses; each book is different and offers something unique to readers, so it cannot be sold the way most products are sold. This presents a challenge, but such a challenge is as unique as the products. How do you brand a book? Or a big, conglomerated publisher? Fact is, it’s a difficult process. We need to look bigger, or smaller: imprints are smaller divisions of a publisher, and authors are bigger “conglomerates” of the books they write. How can these work together to create a harmonious, mutually beneficial relationship?

Branding is a powerful tool, but it must be used in order to be of any use. Publishers underestimate the power of imprint branding, and by doing so, they are letting authors take on more work in branding than they can, or should, handle. Imprints can’t do much without the authors, and authors, while they can do it without traditional publishers, may benefit more from partnering with imprints that create brands that draw readers and support authors. In order for publishers to move forward into a promising future, they need to make changes in how they approach acquisitions and social engagement online and offline. They need to consider how readers discover new books, and implement strategies that allow discovery to happen easily. An imprint that is known for what it produces helps itself and the company, as well as the author and the reading community. Branding is essential to a successful book and a healthy imprint, and publishing professionals need to start creating solutions to the brandlessness that seems to have been plaguing the industry for quite some time.

Works Cited

Anderson, Hephzibah. “How Authors Become Mega-brands.” Culture. BBC, 19 Feb. Web. 16 June 2015.

“Brand and branding” Def. 1. American Marketing Association Dictionary Online, n.d. Web. 7 June 2015.

Charman-Anderson, Suw. “Book Discovery: Give Me Blind Dates With Books.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 28 Mar. 2013. Web. 02 July 2015.

Digital Rights Committee. “The Key to Saving Publishing and New Writers – Branding the Publisher to the Consumer.” Association of Authors’ Representatives, Inc. N.p., 3 Feb. 2012. Web. 17 June 2015.

Gallagher, Kelly. “How to Thrive in the “Golden Age” of Independent Publishing – IBPA Independent.” IBPA. N.p., Aug. 2014. Web. 02 July 2015.

Levin, Michael. “Why Publishers Have the Blandest Brands in All the Land.” The

Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 08 Mar. 2013. Web. 28 Mar. 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michaellevin/why-publishers-have-the-b_b_2837609.html

Royle, Jo, Louise Cooper, and Rosemary Stockdale. “The Use of Branding by Trade

Publishers: An Investigation into Marketing the Book as a Brand Name Product.” Publishing Research Quarterly 15.4 (1999): 4. Springer. Web. 16 June 2015.

Vinjamuri, David. “The Strongest Brand In Publishing Is …” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 4 Mar. 2014. Web. 17 June 2015.

Writer’s Relief Staff. “Why Every Writer Needs An Author Brand.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 30 Apr. 2014. Web. 17 June 2015.

Appendix A – Group/Imprint Divisions by Publisher

Simon & Schuster

Adult Publishing

Atria Books, Folger Shakespeare Library, Free Press, Gallery Books, Howard Books, Scribner, Simon & Schuster, Threshold, Touchstone.

Children’s Publishing

Aladdin, Atheneum Books, Beach Lane Books, Little Simon, Margaret K. McElderry Books, Paula Wiseman Books, BFYR, Simon Pulse, Simon Spotlight.

Audio

Simon & Schuster Audio, Pimsleur.

International

Australia, Canada, UK.

Hachette Book Group

Grand Central Publishing

TWELVE, Grand Central Life & Style, Forever, Forever Yours, Vision.

Little, Brown and Company

Mulholland Books, Back Bay Books, Lee Boudreaux Books.

Little, Brown (Books for Young Readers)

Hachette Nashville

Faithwords, Center Street, Jericho Books.

Orbit

Hachette Books

Hachette Audio

Macmillan

Adult Trade

Farrar, Straus & Giroux (North Point Press, Hill and Wang, Faber and Faber Inc., Sarah Crichton Books, FSG Originals, Scientific American), First Second Books, Henry Holt (Henry Holt, Metropolitan Books, Times Books, Holt Paperbacks, Henry Holy Books for Young Readers, Macmillan Audio, Picador, St. Martin’s Press (Griffin, Minotaur, St. Martin’s Paperbacks, Let’s Go, Thomas Dunne Books, Truman Talley Books, Palgrave Macmillan), Tor/Forge (Starscape, Tor Teen), Flatiron Books

Children’s

FSG Books for Young Readers (under Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Feiwel & Friends, Henry Holt Books for Young Readers, Imprint, Kingfisher, Priddy Books, Roaring Book Press, Square Fish, Tor Children’s (aka. Starscape).

College & Academic

Macmillan Higher Education, Bedford/St. Martin’s, Hayden-McNeil, Palgrave Macmillan, W.H. Freeman, Worth Publishers.

Magazines & Journals

Distributed Publishers

Bloomsbury USA and Walker & Company, The College Board, Drawn and Quarterly, Graywolf Press, Papercutz, Rodale, Page Street Publishing Co., Entangled Publishing, Guinness World Records.

HarperCollins

Amistad, Anthony Bourdain Books, Avon, Avon Impulse, Avon Inspire, Avon Red, Bourbon Street Books, Broadside Books, Dey Street, Ecco Books, Harper Books, Harper Business, Harper Design, Harper Luxe, Harper Paperbacks, Harper Perennial, Harper Voyager, HarperAudio, HarperCollins 360, HarperElixir, HarperOne, HarperWave, William Morrow, William Morrow Cookbooks, William Morrow Paperbacks, Witness.

Children’s

Amistad, Balzer + Bray, Greenwillow Books, HarperAudio, HarperCollins Children’s Books, HarperFestival, HarperTeen, HarperTeen Impulse, Katherine Tegen Books, Walden Pond Press.

Christian Publishing

Bible Gateway, Blink, Editorial Vida, FaithGateway, Grupo Nelson, Nelson Books, Olive tree, Thomas Nelson, Tommy Nelson, W Publishing Group, WestBow Press, Zonderkidz, Zondervan, Zondervan Academic.

Carina Press, Harlequin Books, Harlequin TEEN, HQN Books, Kimani Press, Love Inspired, MIRA Books, Worldwide Mystery.

Audio/Travel/Living Language

BOT, Fodor’s, Listening Library, Living Language, Penguin Audio, Random House Audio, Random House LARGE PRINT, Random House Puzzles and Games, Random House Reference.

Corporate Services and Businesses

PRH Speakers Bureau, Publisher Services, Smashing Ideas.

Dorling Kindersley

DK

Penguin Publishing Group

Avery, Berklet, blue rider press, Current, DAW, Dutton, Putnam, NAL, Pamela Dorman Books, Penguin Books, Penguin Classics, Penguin Press, Perigee, Plume, Portfolio, Riverhead, Sentinel, Tarcher, Viking.

Penguin Young Readers Group

Dial Books, Firebird, Frederick Warne, Putnam, G&D, Kathy Dawson Books, Nancy Paulsen Books, Philomel, Price Stern Sloan, Puffin Books, Razor bill, Speak, Viking Children’s Books.

Random House

Alibi, Ballantine Books, Bantam, Del Rey, Delacorte Press, DELL, Flirt, Hydra, Loveswept, Lucas Books, Modern Library, Random House, Spiegel & Grau, The Dial Press, Zinc Ink.

Random House Children’s Books

Alfred A. Knopf, Crown, Delacorte Press, DoubleDay, Dragonfly Books, Ember, Golden Books, Laurel Leaf Books, Now I’m Reading!, Random House, S&W, Sylvan Learning, The Princeton Review, Wendy Lamb Books, Random House Kids.

Crown Publishing Group

Amphoto Books, Broadway Books, Clarkson Potter, Convergent Books, Crown Archetype, Crown Business, Crown Forum, Crown Publishers, Harmony Books, Hogarth, Image, Pam Krauss Books, Potter Craft, ten speed press, Three Rivers Press, Tim Duggan Books, Waterbrook Multnomah Publishing Group, Watson-Guptill.

The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Knopf, Anchor Books, Doubleday, Everyman’s Library, Nan A. Talese, Pantheon, Schocken, Vintage Books, Vintage Español.

[2] http://www.randomhouse.co.uk/news/2015/03/penguin-random-house-uk-launches-the-scheme-to-find-the-marketers-of-tomorrow

[3] http://www.fastcodesign.com/3031519/how-pentagram-rebranded-the-worlds-largest-book-publisher

[4] http://crownpublishing.com/imprint/broadway-books/

[6] Simon & Schuster and PRH both have similar division; Macmillan was the only Big Five publisher with an academic division.

[7] https://www.youtube.com/user/vlogbrothers

[8] http://aaronline.org/aarblog

[10] http://www.randomhouse.com/golden/

[11] http://graphic-novels-manga.suvudu.com

[12] http://knopfdoubleday.com/imprint/doubleday/

[13] “The Book in the United States Today” (1997), pg. 246